Importance of Plants Domestication

Domestication is a type of animal-plant co-evolution in which morphological and physiological changes were made to certain species, being an example of mutualism (Purugganan and Fuller, 2009). Although us, humans, made the biggest impact on plant domestication, that doesn’t necessarily mean we were the only ones practicing it, or even that we were the first. Some studies show that animals like ants and beetles also take part in domestication processes, particularly in fungus cultures, beginning in some cases roughly 67 million years ago (Farrel et al., 2001; Schultz and Brady, 2008). However, well-documented cases, as the domestications of crops were performed to meet the human needs and, sometimes, even undergoing processes that made plants dependent on humans to survive (Doebley et al., 2006), unlike its wild ancestors.

Plant domestication began 10.000 years ago with a selection made by farmers, of certain characteristics, known as domestication syndrome (Poncet et al., 2004). It was a landmark in our history and the base to the construction of civilizations (Diamond, 2002). Rice, wheat, and maize are examples of plants domesticated a long time ago (Doebley et al., 2006).

Domestication syndrome

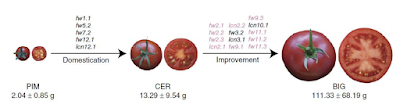

The domestication syndrome is a set of traits that distinguish a new plant from their ancestor (Doebley et al., 2006). Examples of these phenotypic changes are gigantism, greater apical dominance, bigger fruits and seeds, loss of seed dormancy and dispersal among other (Ross-Ibarra et al., 2007). There is no unique way of producing a domesticated plant (Gross and Olsen, 2010), therefore the traits seen today arise from thousands of years of selective pressure in a variety of events (Purugganan and Fuller, 2009).

Domestication centers

There were identified at least half a dozen of domestications centers (fig.1) (Doebley et al., 2006). Trades and migrations contributed to the expansion of the domesticated plants (Purugganan and Fuller, 2009). The majority of the first areas of plant production do not match the present most productive agricultural areas, because in the past those were the areas from which the wild spices were originated, although, with globalization, other areas proved to be more successful in certain species production (Diamond, 2002). This food production explosion enabled the rise of the human species and a technology breakthrough (Diamond, 2002).

Comentários

Postar um comentário